Another parenting lesson

Tuesday, June 4, 2013 at 9:51PM

Tuesday, June 4, 2013 at 9:51PM

So. It's been the kind of day that leaves me mixing peanut butter and powdered sugar in a bowl and eating it straight up. Yeah, kids push me to do things I never thought possible. And not always in a good way.

Today is the day when all of my parenting ideas collided head-on, and in the resulting wreckage, people were hurt.

I have written about Sander before -- about how much I struggle with how to parent him, and about the rules I've had to make for myself to keep me sane and grounded while I'm on this journey.

And still, I have days where I'm just left on the floor at the end of the day, with no reserves of energy or brain power or kindness or cheeriness left, eating peanut butter "cookie dough" and shaking inside at what a disaster it was, and counting the ways I could have done it differently.

This move was hard on all of us, but it was hardest on Sander. He hates change the way cats hate baths. Last week I painted a kitchen stool a different color, to match the new kitchen. He refuses to use it until I paint it the color it was before. That's the way he is -- he likes what he likes. How the hell was I supposed to know that I wasn't allowed to paint a yellow step-stool red?

He hated our new violin teacher on sight. She was organized, together, strict, tidy, and a bit compulsive about obedience and rules.

"Shoes off when you enter the studio. Look at me when you talk, please. No yawning unless you cover your mouth. Oh, dear, tsk, tsk, even Mommy forgot to take her shoes off... That's the second time I've had to tell you about yawning. I know Scout's only two, but she has to learn to whisper when her brothers are having their lesson. That will be a quarter every time you yawn if I have to tell you again..."

Honestly, not a good fit for us at all. She intimidated even me, and I'm usually the overbearing scary one. However: She was a very, very good violin teacher, and after four months with no lessons, we needed to get back into it hard.

My idea was that we'd work with her for one semester. I paid for the semester in advance (my first mistake,) and told her that Sander needed to be coaxed into trying new things.

"Pish-posh. He just needs structure and consistent discipline. He'll be fine with me. Sander has met his match."

After the first lesson, Sawyer was very happy, and Sander was in tears. Sawyer has issues with fine motor skills and needs a lot of help with violin. He's also cheerful, compliant, and sweet. The violin teacher loved him.

Sander? "I'm not going to listen to her, I'm not going to do another lesson, and I'm never going in there again, and you can't make me. And I'm selling my violin."

Fabulous. Now we've been set up for a showdown. This teacher says she knows what she's doing, and that if I let her work with Sander, she'll whip him into shape and he'll be fine. He says that he hates her guts and never wants to do another lesson with her.

My second mistake? I didn't follow my own rules. You know, the one where I say to listen to your kid?

I had this whole thing that if I just pushed him a little bit beyond his comfort zone, made him push his limits a bit beyond "I don't wanna," then maybe he'd be better off in the long run.

But at every lesson, it got worse instead of better. She wanted him to play using all four fingers. "But my old teacher said I only need three fingers."

"Sander, you need to play with four and I don't want to hear another word about it. That's the way we do it here."

Tears. Frustration. Refusal to practice. Bribes were used. A lot. Misery. And there was more of "I paid for the whole semester and it was a lot of money and your brother likes it so we're staying" than I'd ever like to admit.

And still, I insisted that he go to the last lesson today. Despite begging, pleading and tears, I asked him if he could just do one more lesson.

Fine, he said. As long as he didn't have to play with all four fingers.

Fine, says I. The teacher's a Suzuki teacher. We chose this because they're kind. They're easy-going. They're all about playing with love and joy. She's not going to be mean.

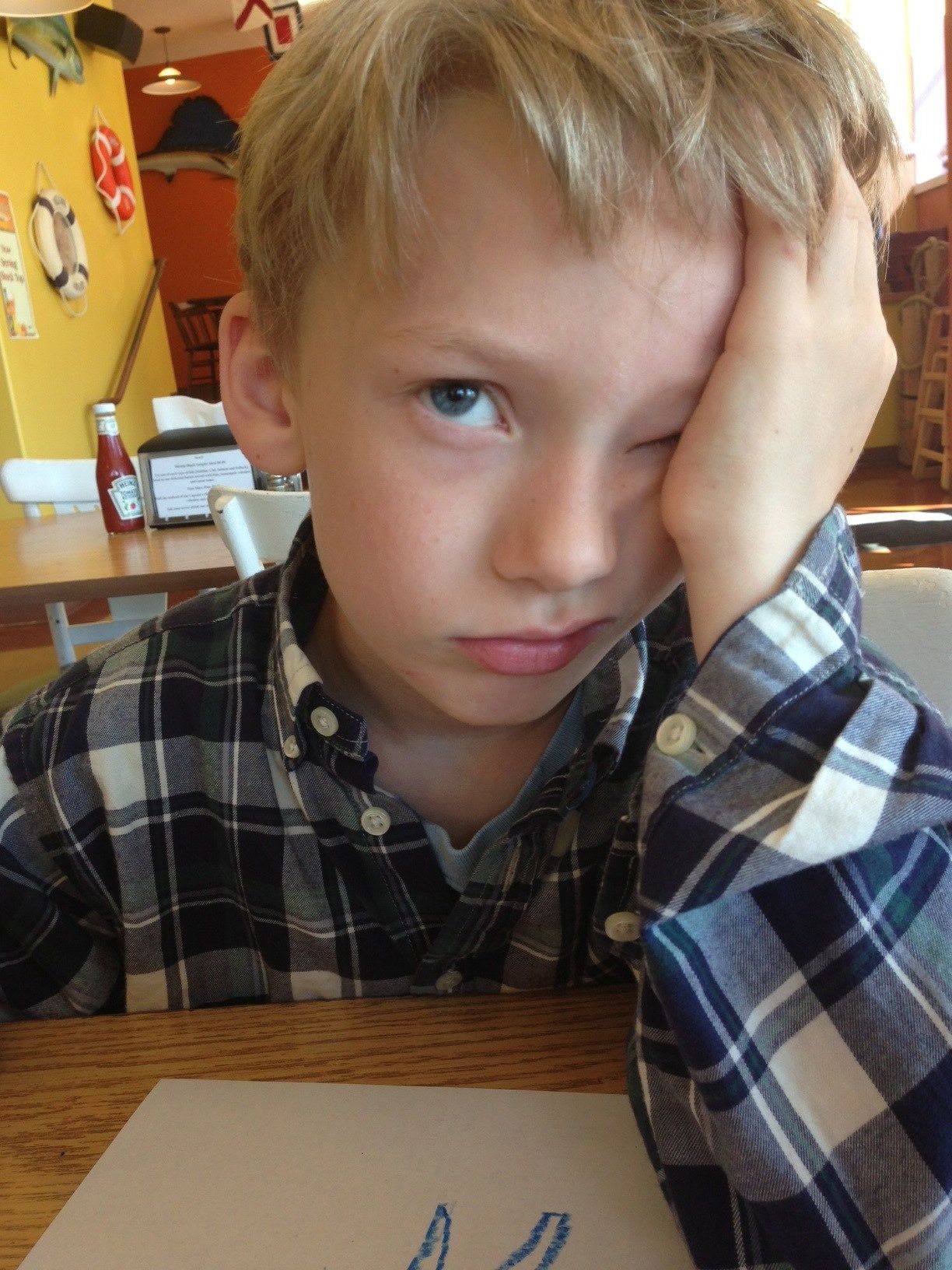

Wrong. It was doomed from the start -- he was hot. He was wearing the wrong pants and was itchy. He couldn't find his violin. He wanted a snack. And when we walked in, he had the look on his face that said, "Find a reason to make me hate you some more."

And when she said, "Play the first song, with all four fingers, please," he wouldn't do it. First, he pretended he couldn't. Then he just wouldn't. Then he just stood there and said, "Nooooooooo."

From there, it went downhill fast.

And that, people, is how my son got fired from violin.

By the end of the session, the teacher asked him to leave and told him not to come back. And she told me that after teaching for 40 years, she'd never had a more disrespectful, disobedient child.

And you know what? I don't care.

Because she broke every rule I had about parenting, and I should have stopped this in its tracks long ago.

It's not disrespectful to say no. It's not defiant to say, "This is too much for me and it's new and I'm overwhelmed and I need you to guide me, not order me."

And if she couldn't hear that in a little boy's cries of "I can't do this and it's too hard," then she's the wrong teacher for my son.

I know there are parents who will say that I should have made him behave -- that this, in its essence, is the fault with homeschooling. That the entire point of education is to learn from difficult people, to learn to adapt to circumstances that are less than ideal, and to learn how to obey when asked.

I disagree completely. The entire point of an education is to learn about how to be a good human being who can find happiness and make the world a better place for other human beings.

Thus, violin lessons. Music, joy, self-expression, self-disclipline to help overcome the tyranny of our own wants and desires. There's nothing in this list about masochism, humiliation, or pain.

And it's my job to remember to have my kid's back. When he says something is wrong, it's my job to listen the first time.

There will be other times when he is faced with something that feels like too much, and I will still have to navigate the fine line between, "Yes, you can do this, go on, even if it's scary," and "I'm making you do something that's way out of your league, and we're all going over the cliff together."

But now, at age eight, I needed to support him, and I took the teacher's side instead of his, and I was wrong.

So, I apologized to the teacher, because she was upset, and because I feel like we did her a disservice. She's a good teacher for many kids, and I should have walked away weeks ago. I apologized to Sander, for not listening. And he apologized to me, for the meltdown.

I told him that I loved him, no matter what. And I asked him if he knew that.

He looked at me and said, "Why do you ask me that? I always feel loved. Well, except by violin teachers who fire me. But I don't need them to love me."

As always, Sander will be fine. That there is a kid who has no problems with self-esteem.

Me?

I'm going to go re-read my parenting rules, remember that it's more important to have a kid who's kind than a kid who can play the violin, I'm going to book lessons with a new teacher, and I'm going to eat a lot more sugar.

Maybe I'll go add chocolate chips to the peanut butter mix...

Sander,

Sander,  autism,

autism,  homeschooling

homeschooling